Memoir is the life wanting to be transformed: It is the life we have been waiting for.

Beth Kephart

The problem with writing memoir is that the person to whom things happened is not there.

Virginia Woolf.

These two quotes, both equally true, but irreconcilable, identify the problem. The transformation of life into art often loses the life. But if there is no transformation there is no art. Only anecdote, or travelogue.

This quandary has rendered me paralysed for six years. And six or more drafts.

Ask a publisher or agent what they seek in memoir, they will tell you ‘Memoir is not autobiography. Memoir takes a slice, not the whole cake.’ That slice will identify a crisis solved; an addiction over-come; a grief surmounted; a marriage survived or justifiably abandoned; a child saved, or an overwhelming new road to Damascus. In short, a job done over a limited span. Mostly ‘triumph over adversity’. Such works inspire, gallop away and make a profit.

Only the famous life is worthy of a whole cake,

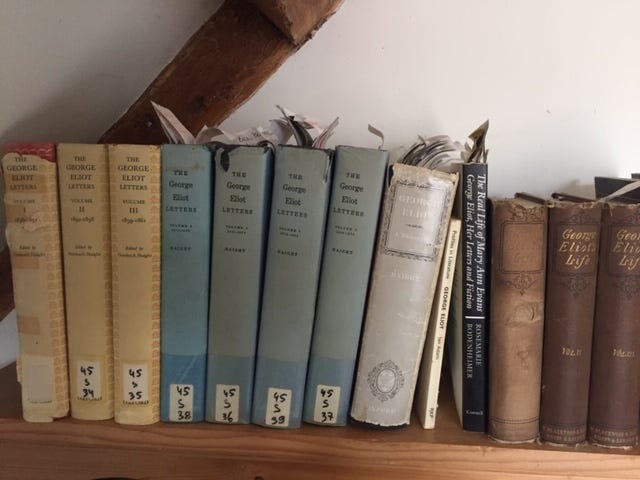

Only the famous life is worthy of a whole cake, and even then, better written by a ‘biographer’ -unless vanity is shameless and uses a ghost writer- and calls itself ‘Spare’. Even a very celebrated author, George Eliot, recognised that ‘If my life is to be written, it is better done for me’. It was done for her, in surfeit: in the ‘magisterial’ biography of Gordon Haight, plus thirty years he devoted to publishing and annotating all her letters. Yet I cannot find her there either. Nor in the many slimmer volumes of her admirers whose breathless eulogies tell you more about them, than George Eliot. Ugly she was known to be, but she was, by decree, the non-pareil of novelists.

Not even in the sanitised and carefully edited three volume biography from her estranged second husband John Cross, who, duty done, never mentioned her again. The ‘not mentioning’ hides a real story, and a more important one, about a woman approaching sixty whose sudden and conventional marriage to him seemed to betray everything she claimed to live by. Yet her speedy death after the marriage also spins a story that will never be written.

The famous sit upon a plinth, and the sun of prestige from the height, tends to blind. They obscure their own light.

Only in her fiction is she to be truly found, and to find her, a reader needs the interpretation afforded by prior understanding of the issues that underpinned her life, illegitimacy, injustice, prejudice, conflict, hypocrisy, loyalty and, in the end, the irksome conformity imposed by fame itself.

Which brings me neatly back to the great chasm yet to be filled, the value of the ‘ordinary’ ‘unfamous’ individual life. Why would anyone be interested?

Michelangelo’s bound slaves emerge from the rough stone.

Suppose you hold a belief —which I do—that each life is a polished and unique manifestation of a perfect creation, to be shaped to a blueprint already drafted. The chronology of that life, its errors, stumbling, relationships, fortuitous gifts, and its deprivations all whittle the slave emerging, as Michelangelo’s bound slaves emerge from the rough stone. Only the whole life will show this patterning, from its conception to its final days. It may never be completed but even lacking the QED, perhaps the remaining uncarved stone still holds its future potential, and perhaps that potential holds its universal relevance. For another birth, another liberated slave? A reader who recognises?

we arrive, each of us, with a mission.

I will commit to an hypothesis—that we arrive, each of us, with a mission. Not a destiny pre-planned, but a purpose that engages our skills, intuitions, and above all longings, for longing seems to energize our search. As children we sense it, and then, as adults, we persuade ourselves that our unfulfilled life negates longing’s value or mocks its illusions. That persuasion goes by the deceptive names of ‘maturity’ and ‘adjustment’, its truer names are disillusion, disappointment and defeat.

Perhaps that is why the acceptable memoirs are usually those dealing with events that remind us of purpose, spring us back to ourself, reset us to the understanding we abandoned? They limit themselves to regarding the new emergent muscles, the waxed contour, and the fine chisel of detail, but rarely stand back to see how the rough unformed life made that emergence inevitable. Only the whole life, the yet-to-be-hewed stone, all the closed doors of false aspiration, explains the emergence of a unique body of thought or work or a new passion pursued. It also limits the life possible, its spread and dynamic. The eventual vocabulary is drawn from sudden emotional growth, the discarding of disappointment, and sometimes the selection of a different sphere of academic or practical expertise.

Thirst is what lowers the bucket.

Choice for something particular is drawn like water from a well. Thirst is what lowers the bucket. The personal life itself creates that unslaked thirst.

Denial is more important in sharpening thirst than munificence. The famous and privileged, on the whole, are denied denial —George Eliot was an exception—which is perhaps why they tend to invent poverty and now, with poverty so widespread, full-blown victimhood. Without fairy-tale beginnings their accomplishments are trivial. Nowadays all high-tech entrepreneurs begin in a back garage, and conceal their Rockefeller or Rothschild bloodlines, as well as their sponsor’s wealth.

The emergence of genius from unpromising beginnings is a favourite theme, but true genius intuits the future, and has little to say about the past. It begs the ultimate question about the nature of individuality, for geniuses hold up the mirror to the irrelevance of the collective. They are not limited by it, as the rest of us are. Their thirst is insatiable and focused.

defining their own uniqueness in their departure from their everyday

Someone once asked me if there was anyone I admired who had an orthodox, perhaps privileged Oxbridge-type education from which (s)he had never deviated? I could not name one. There were orthodox academics who ventured into fiction like the Inklings, C.S Lewis, and Tolkien, defining their own uniqueness in their departure from their everyday; there were many autodidacts who had always known better, and now the new army of alternate thinkers have mostly abandoned their original conformity. They feel liberated by it, albeit rejected by family and friends alike. They are the ones making waves, broadcasting, analysing, truth hounds venturing into fields new to them, abandoning careers and security.

Even my very conventional schoolmaster husband (top scholar, good cricketer, Oxford Historian) at sixty leapt into wild seas, studying and teaching Mathematics instead, and it changed him utterly, open to new conjectures, and reading fiction. He was shocked to find that all his prior admiration of certain historians was better served by philosophy and historical fiction. And many previously revered, were frauds. Mathematics was pure, and a purity of palate followed.

No authority beyond pure thought. No experts, no other opinions.

The ultimate liberty

All converts have a memoir to write, and most would have a hinge that closed the first door for the wider world of bracing adventure. What lay enclosed by that door gave rise to the frenzy for fresh air. Both together are necessary to their story. Eben Alexander published his blockbuster, Proof of Heaven, his near-death survival story because he was a neurosurgeon, although countless Rishis, Brahmins, or whirling dervishes preceded him in knowing what he discovered.

What then of the ‘ordinary life’ (not that any life is ordinary; there is no such thing) as the quintessential fount of common experience. The ‘market’ has yet to catch up, for the marketable book is that which feeds the unexpressed longing in bite sized accomplishments of the ‘job done’. It refuses the rough stone of family, country, generation, culture, all of which shape, and curtail the emerging purpose.

DNA is a spiral coil, coiled precisely to shut out the solubility of water. There is a reason for preserving its integrity. Like any valuable manuscript, it survives better without the penetration of water. DNA encodes but also defines. It encodes the past, the unfulfilled longing, but it also limits the reach of the single recorded life, although that granular life carries its overtones of both past and future, the potential of the yet-to-be-carved stone.

That leaves art unaddressed. Not everybody, even with a good conversion to light a new Damascus, is a writer. What Beth Kephart’s call for the ‘transformed life we have been waiting for’ is asking for, is art. I have read her excellent guides to the writing of memoir, ‘On handling the Truth’ and many others besides. All have useful pointers, largely on the don’ts, but in reading her recent memoir I was still searching for her.

Her art is voluptuous, the phrasing and images near perfection: it was like listening to Beethoven’s last quartets, but with a difference. In Beethoven’s sublime quartets each tune takes its life from its contrast to the one that preceded it, maestoso subsides and giacoso whirls into a frivolous dance.

there is a sustained sear

In Beth Kephart’s Wife/Daughter/Self, a Memoir in Essays. there is a sustained sear. It is the only word that fits the intensity, heat and concentration; rather like an arrested autumn; leaves turning lemon and crisp but never falling. The aspic of too perfect ‘art.’

Her listings of colour and objects painted the contents and moods of every room and each and every landscape, even the landscape anticipated, the teaching about to challenge. Yet in such detail she remained the eye that saw, the writer that selected. Art superseded the life. Transformation can also throttle the drawing of breath.

Only in her teaching exercises, all imaginative and original, did one get a glimpse of her rigourous refusal of the superficial, the tepid, the half thought, or unexamined, perhaps the failure to uncoil the locus of that particular DNA link. Instead, merely to note its placing.

So, go deeper.

Thank God I persisted with her book, for in a final essay about Henriette Wyeth, and Beth’s discovery of their parallel circumstances did Beth herself arise from the page. A testament to the saying (and truth) that the greatest clarity in vision is on the periphery. It is not in the fovea of direct gaze, but on the margins that we see clearly.

That is true of feelings too. We tend to encounter feelings in reflection, or afterwards, and the ‘mot juste’ tantalises, arising almost always too late when the feelings clarify but the appropriate reaction dies, unexpressed.

Her identification with A.C Wyeth and the strains put upon his daughter, Henriette’s marriage, and move away from him, told more than all the observations about her own husband’s conspicuous dishiness and the sharp eyes of other women’s envy. Her own insecurity about her looks and his choice of her were seen better through the eyes of others. Her vulnerability, not her disclosures or analysis, was exposed. At last!

She had been candid about other failings but the candour, like the detail in Durer’s drawings, was so explicit and well argued that candour obliterated pain. One admired but did not shed a tear.

That was one reason I am glad I persisted. The other was finding that Beth Kephart had a secret prior-paragon, whose life had preceded and called to hers. She was fortunate that Henriette Wyeth was a painter and her influence or call lay in the emotional conflict with her father A.C. Wyeth, the parallel tribulation of competing claims on loyalty. Beth understood, for she had faced a similar conflict in her claims of writing; Henriette’s service to painting was a legitimate passion, one that could excuse the failings of a daughter’s obligations to an aging father. It is one many creatively driven women share. In finding Henriette’s homestead, Beth found the painter’s choice of landscape, colour and season. And the absence of her difficult gifted father, whose tragic end she missed, and she also missed his funeral. Art won.

But at a price.

I was glad to discover Beth Kephart through her love for another creator.

I uncovered her, full frontal, sitting solidly within my own family

My paragon was more immediate and less understood, for, as a raw South African, I was merely ‘pretentious’ to be intoxicated by George Eliot, intoxicated enough to leave South Africa for the England she ‘painted’. Its tradition called, its long history, and its poetry. But my story eventually circled back and bit me. A spoiler alert: Perplexed by George Eliot’s inexplicable interruptions at critical junctures throughout my life (and not limited merely to the reading of her books), none of which made any kind of sense from a long dead writer, it was not until exhorted to write a memoir that I uncovered her, full frontal, sitting solidly within my own family. The family she had never met, twelve thousand miles away.

She took off her shoes in 1880 in an opulent house on the Thames and sat waiting to be greeted in 2018 on a lonely farm in the Orange Freestate.

George Eliot, burdened by rather irritating omnipresent stepsons, had, with their father George Henry Lewes, dispatched them to find their fortunes in South Africa. The result? Both young men tragically died, one virtually in my Great Aunt Mary’s arms. The pitiable memorabilia were annotated and returned, and my great aunt and uncle were the conveyors of the news, the pall bearers at a funeral, and shared, thereafter, the god parenting with George Eliot of her two orphaned grandchildren. None of this was known by anybody, not even my grandmother whose aunt Mary died when my grandmother was three.

At sixteen I encountered the first signal of this event when directly bequeathed (by my grandmother), George Eliot’s last novel, Daniel Deronda, signed and inscribed to my great (x3) aunt. To commemorate circumstances that none of the other esteemed biographers ever knew. It offered a critical insight into a childless author’s limitations. Denied children of her own, George Eliot had financed and provided for stepsons whose constant presence, as adults, she found burdensome. But as a stepmother she had to be more careful than a real one would. This was another insight into the call (and seeming selfishness) of the dedicated creative life. Children are relegated by women compelled to serve art.

The link between my family and Eliot took place where I was born and my life began.

I only discovered it through the research and writing of a memoir, and illiterate letters penned from an isolated farm begging for money and grateful for boxes of books, and her stepson riding into Basuto Wars with my ancestral cousins to shoot blacks as casually as partridges —a final nail to explain, and perhaps explode, the call of George Eliot.

It also starkly underlined the hypothesis. Each life comes with its purpose. Mine was to unearth George Eliot’s difficulties as a mother. Hers were the mirror to my own.

My entire life was pointed in George Eliot’s direction, and when finally, it had stripped away everything else, she sat down to uitspan with me at the end of this long safari, led by her and leading finally back to her. The parallels between her life and mine were an almost perfect mirror. Mrs Cadwallader was my grandmother, and my Casaubon tried to kill me. This is where literature and life join hands.

What you read, especially when books are hard to come by, is as ‘shaping’ as the family you inherit or the country in which you are born.

I know that nothing, but nothing was irrelevant in that journey. To do it justice the whole life is necessary. And I am a nobody, and no publisher would touch it, or believe it. Some have already said as much. ‘Very compelling, rather unbelievable, why not write it as a series of short stories?’ Did that agent not notice the title Far Fetched? ‘Do tell me whether you ever had another attack (like Damascus) and what drug was prescribed for it? ‘Write it as a collection of characters and what you learned from each? Many would relate to that.’ ‘Cut out George Eliot entirely: This is not her story.’ (Translation: Don’t try and hang your modest hat on the peg of her prestige!)

Forget the life and attend to publishing conventions.

All can be summarised. Forget the life and attend to publishing conventions. Make our persuasion easier. But that is not the story I want to tell. Mine is more important than that, because it is also the story of every life, its patterns and its prodding. Its guiding DNA, both unique and universal.

One does not dig up a reputation to examine the ring on its pinkie finger. Or give a new work, by a nobody, leave to look at it. George Eliot will remain incarcerated, pickled in a formalin of ‘received opinion’. Hands off.

I was on the point of offering extracts from the most recent draft of the memoir here on Substack, but Beth Kephart’s book has stalled that for the moment. Courage may return. I have learned a lot from reading her memoir, more than from her ‘How to Handle Truth’. But it has given me pause.

Some valuable quotes from her ending.

Because plot bores me and knowing doesn’t, I write to find out what I know.

The gist will do. The gist is enough. Identify the gist and palm on some polish.

Truth is not continuous; stories live in seams.

I agree with all of those. I too write to find out what I know, or think. I am also partial to a good gist. Which is why I write poetry. But a gist cannot convey the loneliness of an unwanted child, nor the call of a country the reader has never seen, nor the power of the books a reader has never read.

‘Seams’ stitch things together. Unlike Beethoven’s music, language has no natural cadences that signal the change of key in a single chord. Silence or bold headings break the action, but lose the seams. My plot is the plot of the self-discovered and slow-revealed life, working to the blueprint of the draft I arrived with, but had to learn to read. Not to mention the improbable assistance from extraordinary people who had no logical reasons to find me. Like the appearance of sudden philosophers in unexpected places who came to give instruction. Out of the blue. Then they walked away. Far Fetched. Indeed.

The problem of writing memoir is the same as the problem of other people. Is any face the definitive face, and do we ever encounter the person who knows what we never can?

I will end with a gist of the dilemma where I currently balance, newly uncertain. Or you can take the pith from what this essay is essaying to say.

Showing the Door.The Woman-who-thought-she-could-write

realised (with her morning tea), on March eighth,that she had been misled.

She looked at Language snoring beside her,

his lascivious tongue flickering kisses...

and wondered what she’d ever seen in him.

In the early days he was lithe and spare:

Lean as a leaf that could cut a thumb.

Moist as an eye in a crucifixion.

The traps he sprung watered cheeks with pearls...

Laughter bubbled unforced.

His seduction had shaved pencils

Spearing dark dreams like bats fleeing light.

Now he sulked, demanded home cooking...

Cracking bones, complaining...

At a desk-top boiling all day.

How had insinuation slithered

(Persuading the Word to ape God?)

between the smooth sheets of a welcome.

The coral brained dish of endeavour

turning black with nicotine.

The Egyptians were content with an alphabet;

awaiting Napoleon, planning parchment or paper?

It was no big deal, sand would suffice.

Millennia passed...

chipping stone, slurping beer.

Talk alone managed to trade and to travel...

The river flooded without self-assembly instructions...

Pyramids made their point, and were proved non-combustible.

Who is Posterity?

What is the fuss?

Her garlanded Bacchus had grown obese

snorting lines of attention; sweating metaphors sweet,

astride his tortoise, bibulous, self-serving,

as flaccid as the spittle sliding down

his

chin